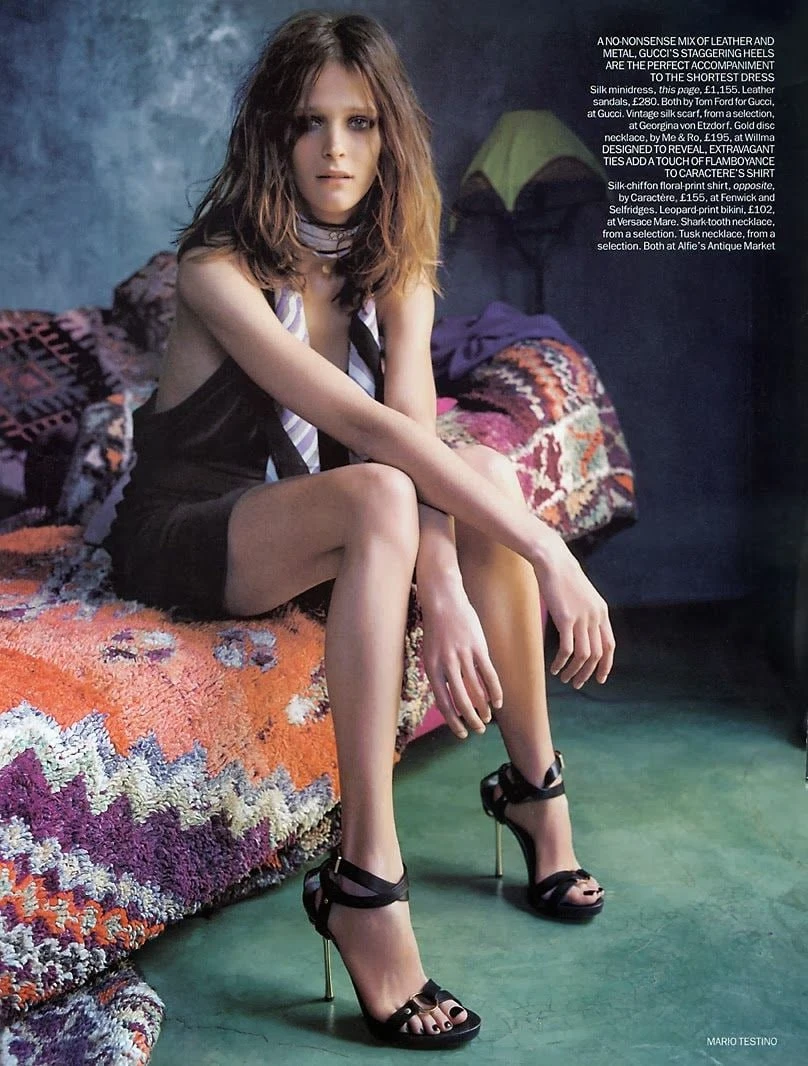

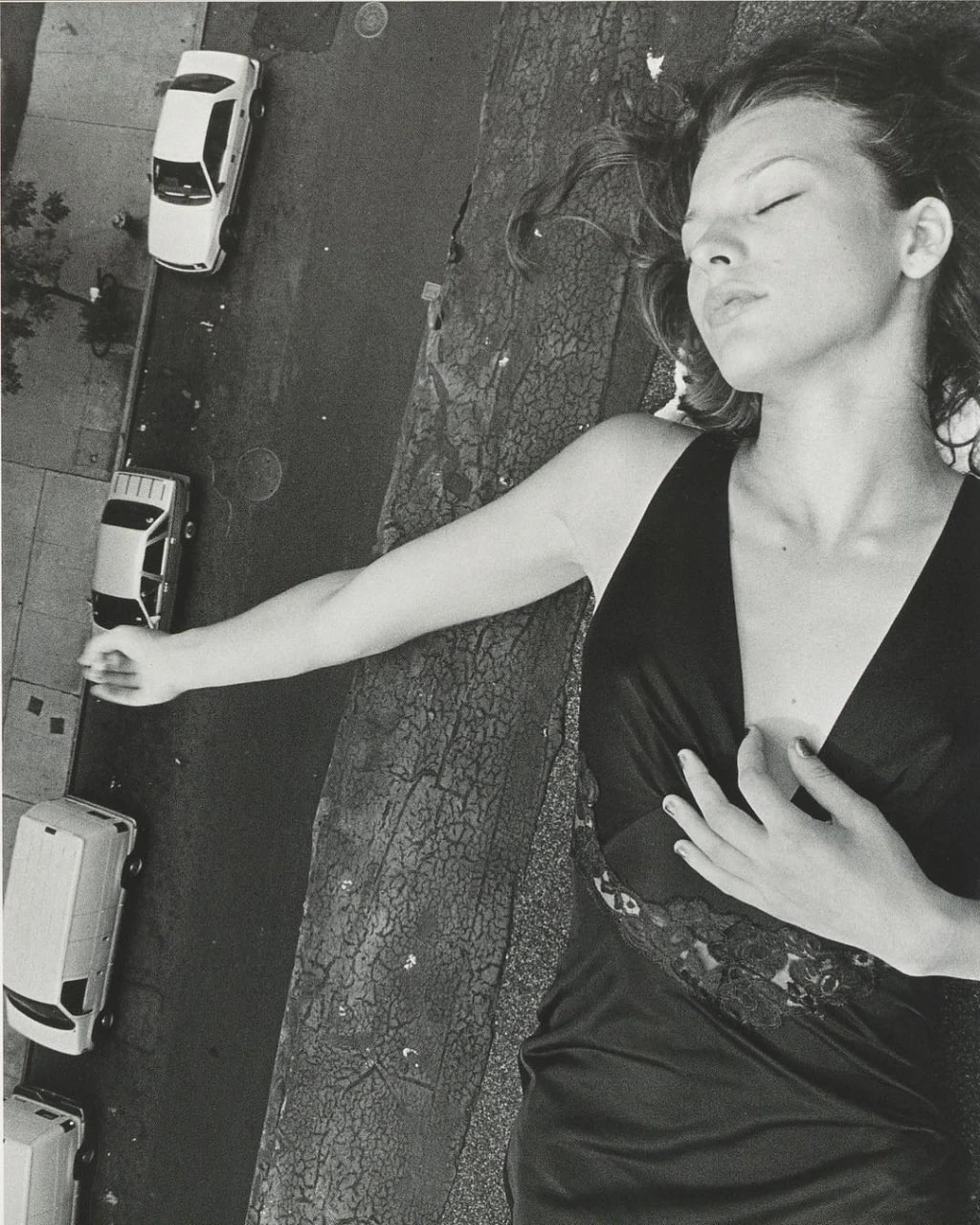

Do you remember the mid-90s? Glossy magazines suddenly shifted to a new cult of beauty — pale, fragile faces, skinny bodies, messy hair, and eyes that seemed to come from another world. Models looked as if they had just endured a sleepless night and stumbled straight from the street onto a magazine cover. This was called heroin chic. Nobody openly promoted drugs, but the resemblance to their devastating effects was impossible to ignore. The glossy pages filled with images where youth looked drained and indifferent, while clothing became part of this gloomy mood. Photographers brought the language of gritty street realism into high fashion, and brands eagerly thrived on the controversy, basking in the spotlight.

But in 1997 everything changed abruptly. Young photographer Davide Sorrenti, whose work had become symbolic of the style, died from complications of a chronic illness. His death became the trigger for fierce criticism. His mother, Francesca, openly spoke out against the romanticization of addiction and the exploitation of underage models. And then politics intervened. On May 21, U.S. President Bill Clinton addressed the press, declaring that the “glamorization of heroin” was “ugly and destructive.” His words spread across global media, and the term heroin chic ceased to sound like a trend — it became a warning.

The era wasn’t erased, but the rules shifted. Magazines began choosing images more carefully, brands worried about their reputations, and agencies debated codes of conduct and the boundaries between art and exploitation. The aesthetic of “exhausted beauty” wasn’t entirely abandoned, but it was handled with far more caution.

Since then, one truth has remained: once a photograph leaves the studio, it stops being just an image. Any dark aesthetic in fashion is judged not only for its visual impact but also for the human cost behind the illusion.

You may also like: