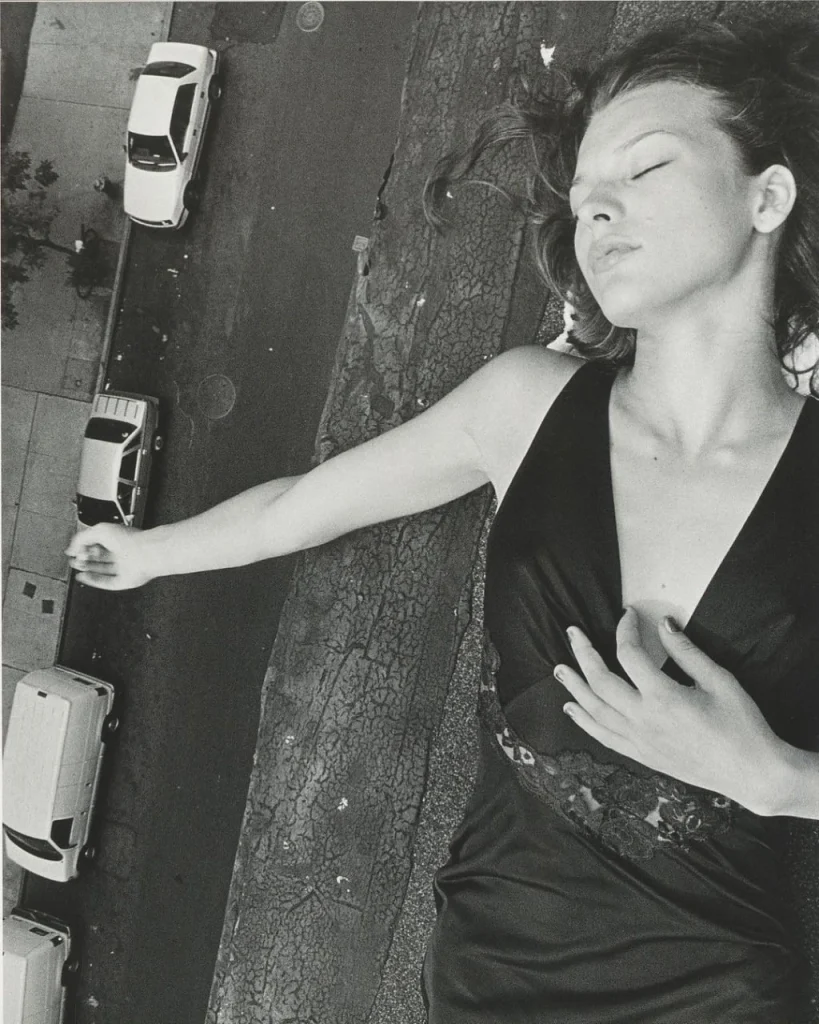

Remember the mid-nineties? Back then, glossy magazines suddenly switched to a new cult — pale faces, thin bodies, messy hair, and a gaze that seemed to come from another world. Everything looked as if the models had just stumbled out of a sleepless night and ended up straight on a magazine cover. That was heroin chic.

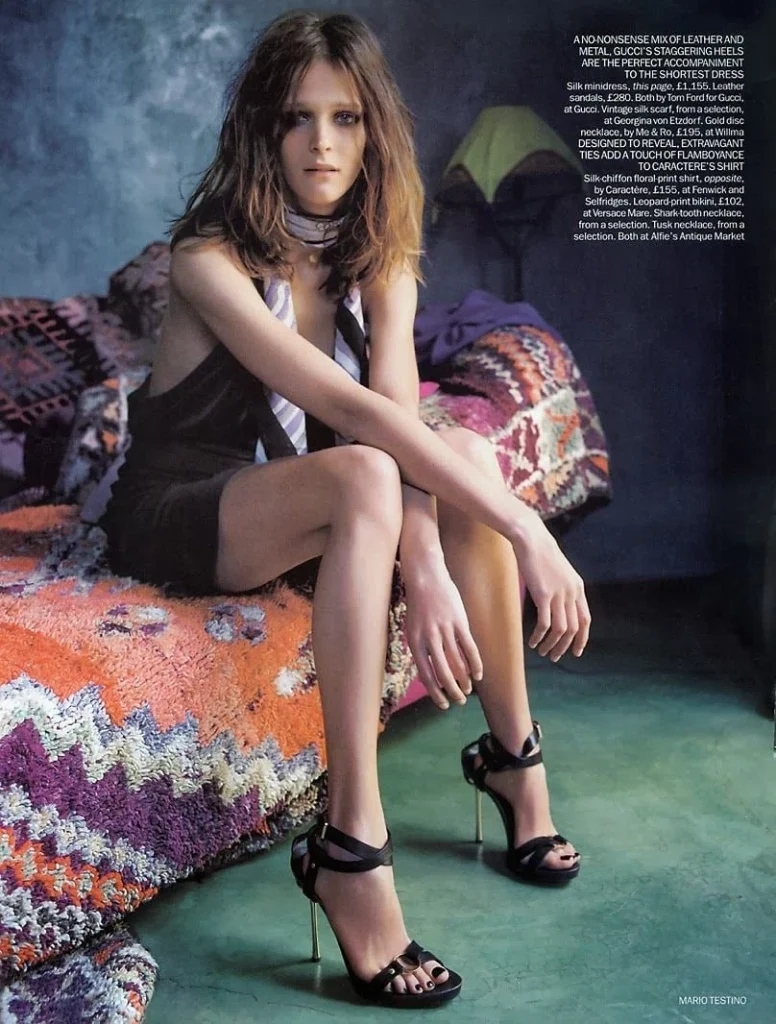

No one openly promoted drugs, of course — but the resemblance to their consequences was impossible to ignore. Fashion spreads showed youth wrung dry, and clothing became part of that hazy, fragile mood. Photographers brought the spirit of street “dirty realism” into high fashion, and brands basked in the noise and attention it created.

But everything changed abruptly in 1997. Young photographer Davide Sorrenti — whose images had become the very symbol of the style — died due to complications from a chronic illness. His death triggered a wave of public backlash. His mother, Francesca, spoke out against the romanticization of addiction and the use of underage models.

Then politics stepped in. On May 21, U.S. President Bill Clinton addressed the press, declaring that the “glamorization of heroin” was “ugly and destructive.” His words echoed around the world, and the term heroin chic stopped sounding like a trend — it became a warning.

That era wasn’t erased, but the rules changed. Magazines became more careful in their photo selections, brands started thinking about reputation, and modeling agencies began debating codes of conduct and boundaries of responsibility — where art ends and exploitation begins. The “tired beauty” aesthetic wasn’t entirely discarded, but it began to be used much more cautiously.

Since then, one thing has been clear: the moment a photograph leaves the studio, it stops being just an image. Any dark or melancholic aesthetic in fashion is now judged not only for its visual effect, but also for the real-world cost that someone might have to pay for it.

You may also like: