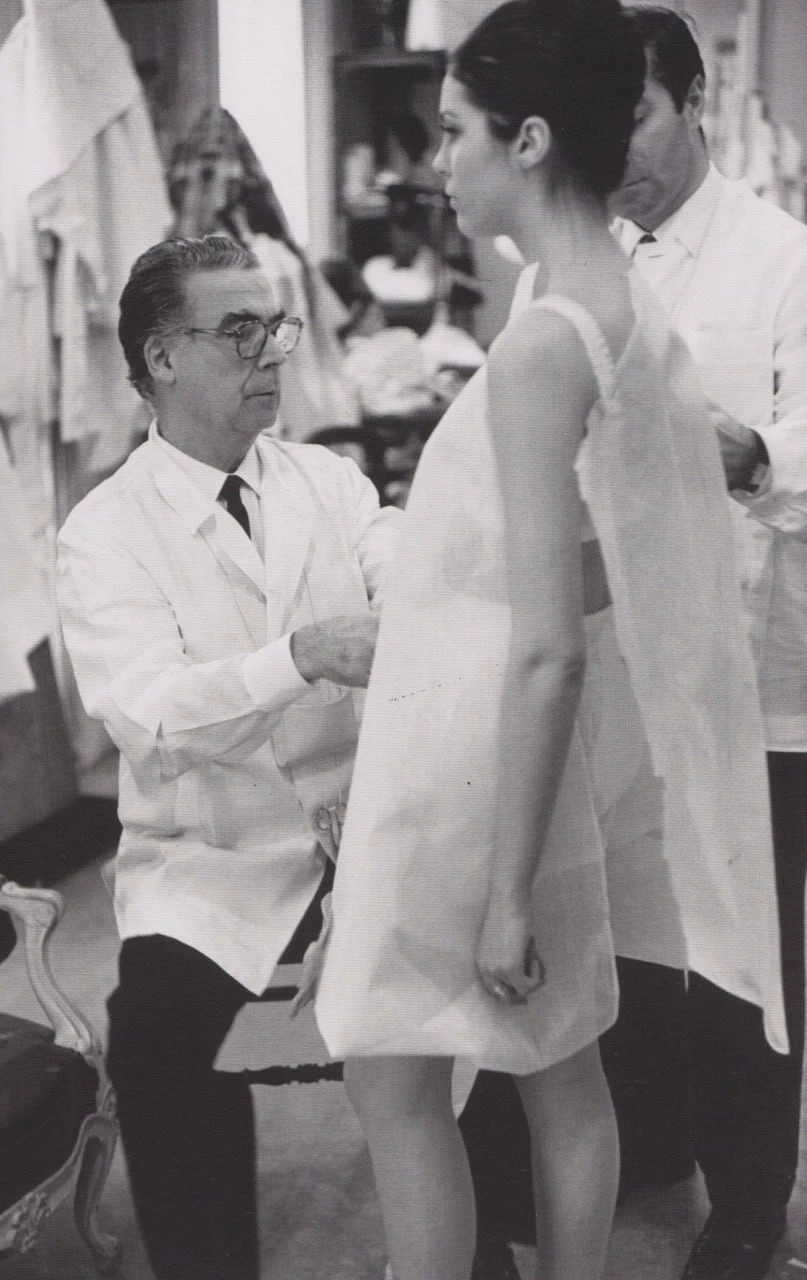

When the fashion world had exhausted its old codes, Balenciaga responded not with a loud manifesto, but with the silence of fabric. Born in the Basque town of Getaria and raised beside his mother’s sewing machine, he stepped onto the Parisian stage already a master — one who felt fabric the way a sculptor senses marble. He didn’t just sew — he sculpted. Each dress became a self-contained form: no excess decoration, no embellishment, no fuss. Just line, volume, and movement — as if the garment had been carved from air.

The Free Silhouette as an Aesthetic Statement

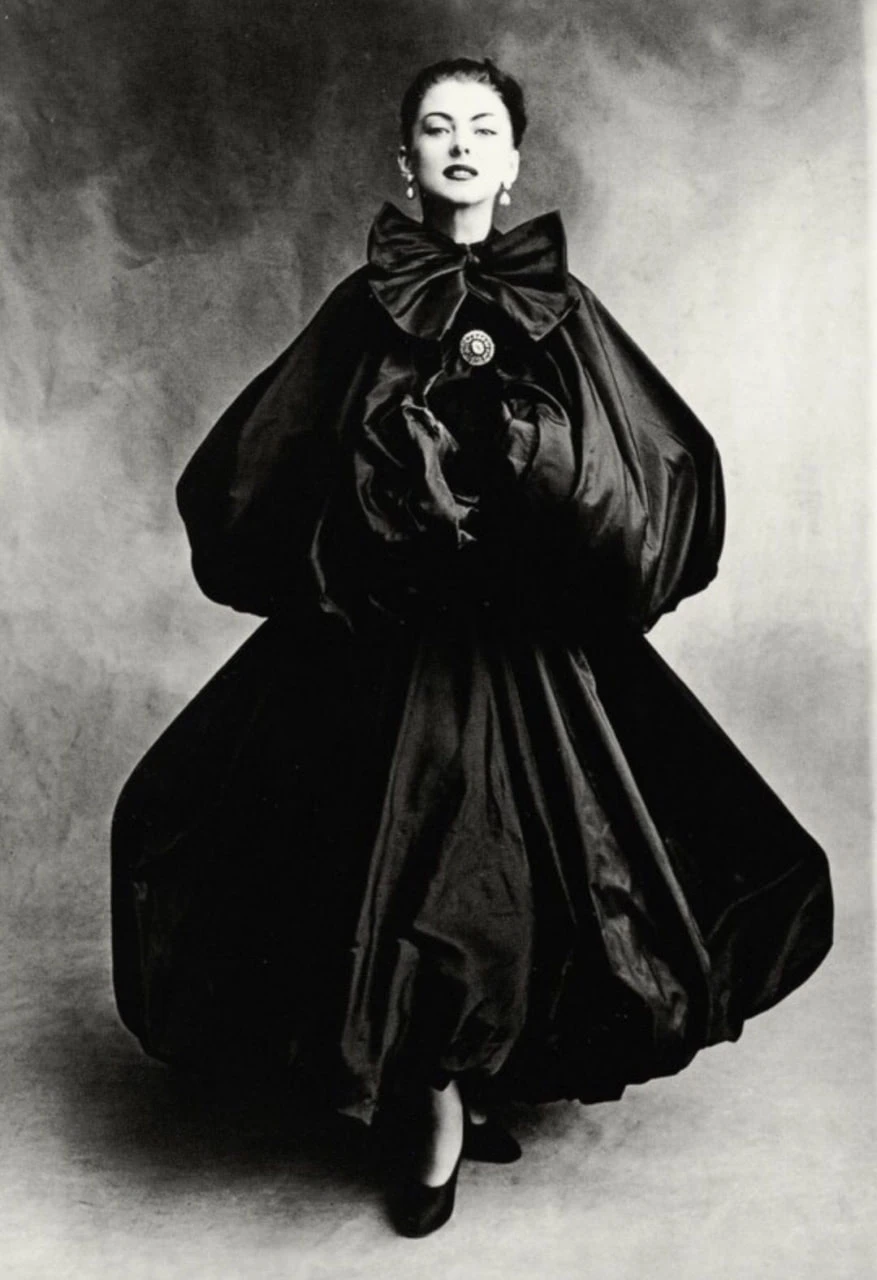

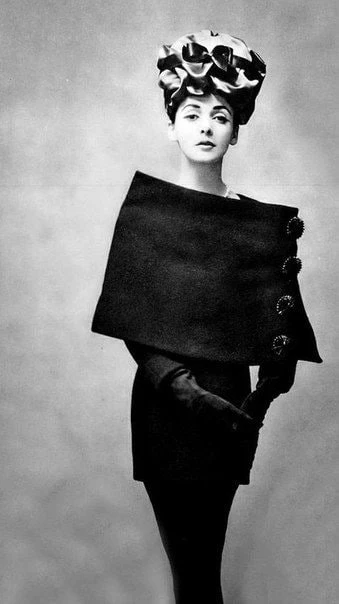

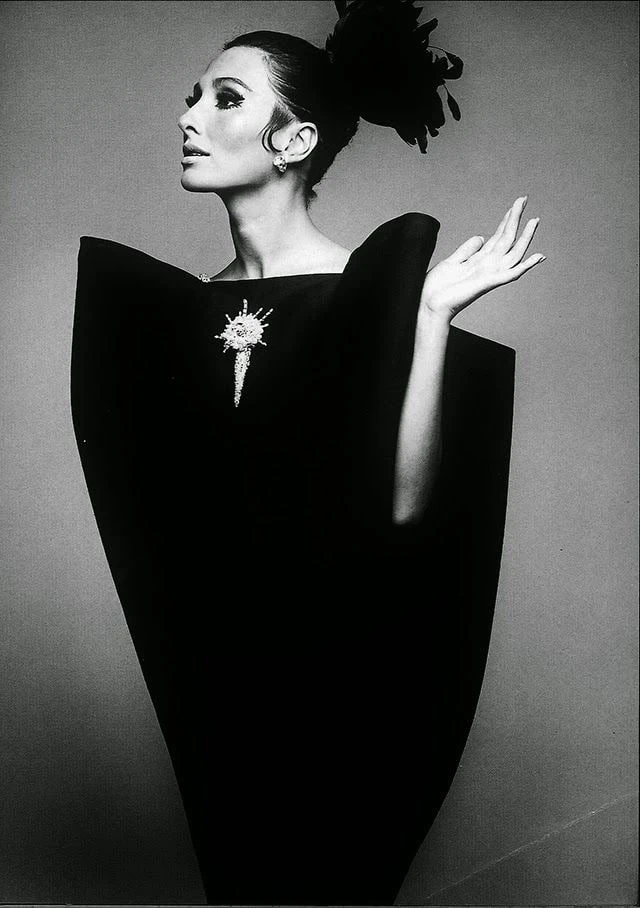

In the 1950s, he began dismantling the rigid waistlines of the era — corsets and constricting forms were left behind. In their place came cocoon coats, “bubble” dresses, tunics, sack dresses, and baby-dolls. These garments didn’t restrain a woman — they enveloped her in light, almost fluid architecture. Everything relied on hidden geometry: fine darts, perfectly balanced linings, and meticulously calibrated proportions. A woman looked effortless, yet every step she took moved through a space crafted with mathematical precision.

Fabric as a Continuation of Thought

To Balenciaga, fabric wasn’t just surface — it was a tool. In collaboration with the Swiss textile house Abraham, he developed gazar — an extraordinary silk, both dense and light, holding shape like a skeleton. With gazar, he realized his boldest concepts: envelope dresses, minimalist capes, and voluminous jackets that seemed to float, untouched by gravity. This material became the language through which he expressed his most complex ideas.

A Precedent for Disciples

Balenciaga’s peers didn’t just respect him — they revered his discipline. André Courrèges, who trained under him, later admitted that the maestro’s philosophy of form became the cornerstone of his own minimalism. Even in the 1960s, when fashion was overtaken by youth and flamboyance, Balenciaga’s creations felt more modern than the latest trends. His forms transcended the fleeting distractions of ornament.

A Legacy Carved by Time

When Balenciaga closed the doors of his House in 1968, it was as if he placed a full stop at the end of an era — a time when fashion was born not in branding, but in the atelier, with chalk on fabric and a needle in hand. His patterns are architectural blueprints still studied and sewn today. His message was simple: clothing is not just a cover for the body, but a space where the body breathes, moves, and lives. Like any building, it must respond to light, weight, curve, and shadow.

Thus the man fades — but the form remains.

You may also like: